Flowing; Paris Fin de Siècle: flooding contrasts in the Paris of end 19th ce.

By Jo Phillips

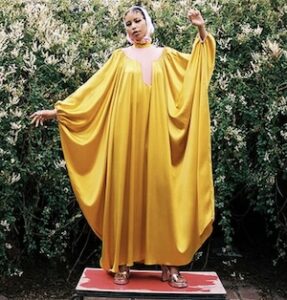

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC

Jane Avril

1899

Color lithograph

55.5 x 37.9 cm (21 7/8 x 14 15/16 inches)

Private collection

When we think about the Paris of the end of the 19th century we usually think of a city that became the emblem of Europe for its progress in all the fields and for its cultural influence. We have the beautiful images about the life of the ‘bourgeoisie’ or middle class of the ‘Belle Epoque’ (beautiful period); women with fancy and luxurious clothes, worldly events in famous bars and cafés, the joy of a new style of life imbued with pleasure, relaxation and amusement.

However, this is only one side of the coin.

“Paris Fin de Siècle” is an exhibition that shows also the other half other coin, in which political, cultural and social upheaval took place in the capital of France. Fin-de-siècle Paris, and France itself, were characterised by many changes and transformations. Especially in 1890s there were social problems and economic crises that caused the rise of conservatism and radical left-winged groups. A hard climate developed, especially after the assassination of the president Sadi Carnot and the unlawful conviction for treason of Alfred Dreyfus.

This situation elicited a notable polarization in all the fields. This polarization was like a flux of contrasts that flowed all over the country: bourgeois and bohemian, conservative and radical, Catholic and anticlerical, anti-republican and anarchist.

The exhibition mirrors the aspects of this anxious, unsettled era, a period in which diverse artistic movements developed. The pieces exposed deal with the late 1880s generation of artists that included Neoimpressionists, Symbolists, and Nabis. It includes artists such as Paul Signac, Odilon Redon, Pierre Bonnard, and Henri de Toulouse Lautrec.

FÉLIX VALLOTTON

The Stranger (L´étranger)

1894

Woodcut on paper

22.4 x 17.9 cm (8 13/16 x 7 1/16 inches)

Private collection

Indeed, the most fascinating aspect of the exhibition is probably the intertwinement between these different artistic movements.

The pieces of the Neoimpressionists, such as Signac, Pisarro or Cross, display a revolutionary painting technique based on the juxtaposition of individual pigment strokes to display an intense single hue. Neoimpressionists made unified compositions with complementary colours and melliflous forms. The light is conveyed in its shades, in its scientific studies when refracted by water, filtered thorough atmospheric conditions or rippled across fields. The depiction of working classes is another concern, as most of the Neoimpressionists had left-winged political views. However, apart from the political objectives, a formal quest of harmony is graspable in their shimmering representations of cities, suburbs, countrysides and seasides.

HENRI-EDMOND CROSS

The Promenade or The Cypresses (La Promenade or Les cyprès)

1897

Color lithograph

image: 28.3 x 41 cm (11 1/8 x 16 1/8 inches)

sheet: 43 x 56.8 cm (16 15/16 x 22 3/8 inches)

Private collection

PAUL SIGNAC

Saint-Tropez, Fontaine des Lices

1895

Oil on canvas

65 x 81 cm (25 9/16 x 31 7/8 inches)

Private collection

The Symbolists, such as Redon or Denis, on the other hand, focus their art on the search of the transcendent. Symbolism at the beginning emerged as a literary movement in the 1880s. Then its principles were codified in 1886 when poet Jean Moréas published the “Symbolist Manifesto” in the French newspaper Le Figaro. In the field of art, Symbolists had anti-naturalistic features in common. They were artists who lost faith in science, since it failed to alleviate the ills of modern society. They rejected materialism, they denied reality as objective, believing in a sort of hidden spiritual reality enshrined in the appearances. In fact their main concerns revolved around spiritualism, states of mind and evocative, dreamlike images. Their representations conveyed the ethereal instead of the concrete, the fantastic instead of the factual, all in the framework of mythological and religious themes, of the dark world of nightmares or the deep psyche of the mind.

ODILON REDON

Pegasus (Pégase)

Ca. 1895-1900

Pastel on paper

67.4 x 48.7 cm (2 9/16 x 19 3/16 inches)

Private collection

MAURICE DENIS

April (The Anemones) (Avril [Les anémones])

1891

Oil on canvas

65 x 78 cm (25 9/16 x 30 11/16 inches)

Private collection

©Maurice Denis, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2017

Then, last but not least, there is the art movement of the Nabis, together with the print culture of the 1890s. Printmaking flourished in France with the mark of characters such as Toulouse-Lautrec or of the Nabis artists. The latter were mainly inspired by the Synthetism of Gaugin, based on flat colours and patterns, and by the two dimensional Japanese prints. Printmaking was a ‘low’ art exempt from academic rules and for this reason it provided more freedom to the artists. The Nabis made posters, prints and illustrations for journals like ‘La Revue blanche’. Toulouse-Lautrec instead worked on city life subjects for posters and advertisements that caught the eye of the passers-by. He made sorts of caricatures depictions of bohemian venues and performers such as La Goulue (The Glutton) or Jane Avril.

GEORGES SEURAT

Caretaker (Concierge)

1884

conté crayon on paper

32.3 x 24.5 cm,

Private collection

PAUL RANSON

The Young Girl and Death (La jeune fille et la mort)

1894

Graphite and charcoal on paper

55.2 x 33 cm (21 ¾ x 13 inches)

Private collection

Although apparently disconnected, these movements have some features in common and in their contrasts and similarities they seem to follow the same path; the artists’ will to grasp a fugitive moment of contemporary life led to the creation of highly crafted works that seem not to have naturalistic hints. The form and execution of the pieces convey an anti-naturalistic composition where emotions, feelings and psychological elements are elicited. The contemporary background of landscapes, cities and leisure-time activities is treated with an introspective eye and familiar objects are imbued with fantastical and spiritual hues.

If you want to be flooded by the diverse and contrasting features of the Paris of the end 19th ce., don’t miss the exhibition in Bilbao that runs from 12 May till 17 September 2017.

Further information is available here: