Tributes: Homage in Film

By Jo Phillips

Film, as with many other art forms, is informed, refreshed and reinforced by that which has gone before. And modern filmmakers are invariably influenced by those directors they looked up to when first becoming interested in film.

Tributes to filmmakers and films can take many forms. Referencing may be the most direct, yet least personal way. A common example is what has become known as the ‘Vertigo shot’ where the camera both zooms in and tracks back at the same time creating a disorientating disjunction first popularised by Alfred Hitchcock in the film of the same name. This referencing is more of a cinematic shorthand by a director or writer, as if to say “I’ve seen this or that film”.

Quentin Tarantino is a notorious ‘referencer’, where with each new film he gives the spectator a guided tour of his exploitation DVD back catalogue. In this way Tarantino is the quintessential postmodern director using bits and bobs from the cinematic scrap heap – even reusing soundtracks from earlier films (usually by Ennio Morricone) – to tell a ‘new’ story.

Other types of tribute could include parody, usually a comic imitation of the serious original, such as the work of Mel Brooks (Young Frankenstein, Blazing Saddles), representing a love of that which is being copied at the same time. Then there’s pastiche, which tends to borrow techniques and forms without the comedic undercurrents of parody.

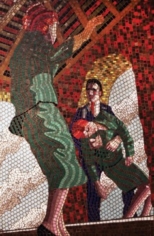

Pastiche is one constituent of Todd Haynes’ film, Far From Heaven (pictured above). He takes the colours and sounds of 1950s melodrama and painstakingly reconstructs the look and feel of the bygone genre. Far from the unfeeling connotations pastiche implies, Far From Heaven is put together in such a loving way that it comes closer to the pinnacle of cinematic tribute; the homage.

Haynes’ framework is the melodramas made by Douglas Sirk in the 1950s, specifically All that Heaven Allows starring Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson. It centres on a middle class widow and mother of two who lives in prim-proper suburbia. But when she starts seeing the family gardener, the social mores close in and she becomes alienated. Haynes, however, takes undercurrents from those films that were subject to strict censorship and makes them explicit, namely racism and homosexuality.

In Far From Heaven Julianne Moore plays Cathy Whitaker, the perfect suburban housewife. Similarly to All That Heaven Allows, Cathy befriends her gardener, Raymond (Dennis Haysbert), the difference being that this time he is black. And it isn’t long before the shiny gloss of her American suburban married life is tarnished when she discovers that her husband Frank (Dennis Quaid) is gay. As a result, she grows closer to Raymond as Frank undergoes ‘corrective therapy’ and Cathy gradually becomes ostracised from the community.

Far From Heaven is a beautiful, painful film. Haynes uses the genre framework, not only to reconstruct the past, but to make it function as a means of highlighting that which could not be shown in the 1950s. It is a tribute, an homage, with purpose and intent that is judged brilliantly by the measured performances, colour-saturated cinematography and Elmer Bernstein’s throwback score.

Film tributes need not be self-indulgent (although, the worst of Tarantino’s work can be thought of as just that) throwaway nods to films nobody has heard of. Instead they can use genre as a celebratory and exercise in reinvention.