Speaking In Code

By Emily Zoeller

How Bona to vada your dolly old eke! Unless you are familiar with the sublanguage Polari it’s doubtful much of that makes any sense whatsoever, here this sentence means ‘nice to see your pretty old face’ Communication is core to human relationships, whether it is via a common tongue or via sub-cultural communication. We understand the common parlance we communicate with grows, changes and adapts with time. But there are some forms of communication that are very much driven by subcultures, cultural identity or even place of birth and although they are still a language they tend not to change or adapt that much. Sometimes key phrases may well end up in the mainstream, and these coded words become general language. But where did so many of these start and why and for that matter, how many of these are still living and thriving? Read more here in Speaking In Code.

‘The Cuckoo Theory’ which may not be commonly known actually lies in a simple theory, being one perception of how humans came to talk. Early theorists proposed the idea that the spoken word originated from humans’ imitation of animals and birds. These noises and sounds animals made indicated to ‘early man’ that we could ‘speak’ to each other.

Community and identity go hand-in-hand when it comes to talking about language. It’s organic, changing and evolving over time. Sublanguages are used in many people’s everyday lives, though we may not think about it, having used them so often it is embedded in our brains.

Modern-day text abbreviations and game dialogue have offered people a chance to keep this same sense of community. When texts could only be 160 characters long, it wouldn’t be uncommon to see classic phrases changed to abbreviations. As LOL (laugh out loud) was used commonly, other abbreviations now also make appearances in daily messages and exchanges between people of all ages. This ‘text slang’ has been nuanced as we went from brick phones to slimline phones, and can actually be considered a sublanguage in itself.

But sublanguages can originate from completely different means and needs. Think of marginalised groups who have adopted a set of words or phrases of even full language to identify themselves and preserve a tribe in times of conflict, and trouble, but others come again for modern culture. Many sublanguages aren’t even full languages; they are merely certain phrases that are translated.

Perhaps you’re a fan of Star Trek. If so, maybe you speak Klingon. This is the language spoken by the humanoid species named Klingons in the popular franchise. A mix of sounds and general gibberish to the common ear, yet for fans of Star Trek, this is nothing unfamiliar, as it is the most commonly spoken fictional language in the world.

However, although there is such thing as The Klingon Language Institute, it’s quite difficult to speak fluent Klingon, as d’Armond Speers discovered. He raised his son Alec to speak Klingon as well as English, but struggled due to the fact the language did not have words for common objects like ‘table’. Since then Klingon has developed words for these.

What if a language you’ve spent time trying to translate ended up being actually absolute gibberish? Well, fans of The Sims may well be surprised if they didn’t already know. Simlish is the language of the EA game. Although many have widely tried to translate the dialogue of the online phenomenon.

Yet, creator Will Wright actually admitted that the ‘language’ is gibberish. Pure nonsense is used instead of English to avoid being repetitive for players. This doesn’t stop fans from creating the odd translation, referring to when the dialogue is used in the game; when someone is happy, a greeting for example. Even some singers such as Lily Allen have ‘translated’ their popular tunes into Simlish for the game.

Both Klingon and Simlish originate through fans of the series or the game, meaning that a lot of sublanguages actually gain popularity and a community through entertainment. Speaking these sublanguages allows people to feel like part of a tribe.

Would you Adam and Eve it?! Sublanguages can also show a community within an area. If you live in London or have even travelled there before, you probably will be aware of Cockney Rhyming Slang.

In theory, if you are ‘born within the sound of the Bow Bells’, the church bells of St Mary-le-Bow in Cheapside, the East End of London, you are a true Cockney. Here, in the late 1700s, crime was a popular activity in the community.

With no police around, nobody was there to stop these illicit activities. It wasn’t until Robert ‘Bobby’ Peel introduced the Metropolitan Police in 1829, meaning criminals had to find a way to conceal their rather naughty activities from the ‘bobbies’ that, these coded words were what became Cockney Rhyming Slang.

A way of speaking in code to hide from authority eventually became widely used in today’s society, to warn people privately when there were ‘bobbies on the beat’ (police in the street).

St Mary-Le Bow Image by National Churches Trust on Flickr https://flic.kr/p/22rCjQm

After that, the local community picked up on this clever rhyming slang, introducing phrases such as ‘cream crackered’ (knackered) and ‘lemon squeezy’ (easy), which we still hear today. You’d be surprised just how many phrases originate from Cockney Rhyming Slang, and how many abbreviations we know and love come from such phrases.

But what if some languages weren’t just words? Welcome to La Gomera; an island within the Canary Islands where some native people speak in a sublanguage consisting purely of whistles, called Siblo Gomero. The people of La Gomera started to teach this language in schools in 1999 after it was used for religious occasions and festivals within the community.

With a small population of just 20,000 people, at first Siblo Gomero was labelled as the ‘language of peasants’, traditionally banned by parents of well-off families. There is now a whole generation of children that don’t know the language, after their ancestors started to emigrate to South America, therefore losing their use for Siblo Gomero as they moved away from the little island.

The language shows heritage, culture, and preserves the art of communication within a tribe of people. Plus, it stands out as being a language that doesn’t need to be actual words to be understood. It’s almost like a code for the people of La Gomera to communicate and speak to each other, without succumbing to using traditional wording like other languages.

La Gomera Image by Enric Rubio Ros on Flickr https://flic.kr/p/2n6vkcM

The island is not the only place where sublanguages exist within an area. Jamaica’s popular Patois language also conveys a sense of community. A lot of native Jamaican people will be very aware of Patois and it’s not too difficult to understand.

The language uses a lot of phonics (the alphabet sounds like ‘hay, bee, cee, dee’) and examples such as ‘mi run’ (I run). It’s unlikely tourists will be able to speak convincing Patois as it takes many years living with locals to perfect, making the sublanguage one of many that convey identity within a certain area.

WikiTongues: Venecia speaking English and Jamaican Patois

However, sublanguages did not always originate through entertainment or in native areas. Sometimes these languages are introduced for the protection of marginalised groups.

Let’s step back in time for a moment. Ashkenazi Jews (Jewish people from Eastern Europe) were forced to live in a designated area called The Pale of Settlement, where German and Slavic languages came together, mixed with Hebrew. A place where Jewish people lived after their mistreatment in Russia and other Eastern European countries between 1791 and 1917 when these areas were run by the Russian Empire. A place of economic bleakness. This is where Yiddish was born.

Colloquially known as ‘mother tongue’, Yiddish is the language spoken by these Jewish people. Now, Yiddish is split into two forms: Eastern (Ukrainian, Romanian, Polish dialects) and Western (German, Swiss, Netherlandic dialects). This was a way in which Ashkenazi Jews were able to communicate with each other in times of trouble, introducing a community within the Jewish people of the two countries. The Jewish communities in Spain before the Inquisition had their own version, Ladino.

As these communities escaped the pogroms and hatred by moving to the UK the USA and further, they took this spoken word with them. As they integrated into new areas, key Yiddish words became part of the common parlance in their new homes.

Yiddish is actually a full language with theatre, books and films all made in the language. For example, the 2009 film A Serious Man, directed by the Coen brothers, has a starter film spoken in Yiddish (with options in English subtitles). There is also books, such as Alan Weber’s The Mensch, which takes elements of old spoken Yiddish mixed with modern day references, following the lives of three generations. This book follows Stewie, aspiring to be a “superhero”: ultimately the Mensch.

Yiddish is still spoken fully in some traditional Jewish homes of Eastern European descent.

Yiddish Literary & Dramatic Society 1923 Image by Ross Dunn on Flickr https://flic.kr/p/qnCf23

Another example of a language used for protection was Polari. From the early 1900s all the way to the end of the 1960s, it was illegal to be homosexual, and these men involved in what was then illicit illegal affairs found a way to secretly communicate with each other to avoid suspicion from undercover police and the anti-homosexuality laws.

This secret language was made up of Italian and Romani phrases, later evolving to add Yiddish as well as rhyming slang. It is known as Polari, the name coming from the Italian word ‘parlare’ (meaning ‘to talk’). The language was originally used in circuses and the Navy. People who spoke in Polari would often shorten words, similar to Cockney Rhyming Slang, such as ‘Irish’ (wig) which rhymes with ‘Irish jig’, hence the abbreviation.

And it doesn’t stop there. Still to this day, although you may not realise it, a lot of modern films and music use Polari phrases. For example, David Bowie’s ‘Girl Loves Me’; the song from his Blackstar album is written half in Polari and half in Nadsat, (another slang language used by the protagonist in A Clockwork Orange a book by Anthony Burgess), and the film Velvet Goldmine?? (1998) also takes elements of Polari, specifically in a club scene of the film, using subtitles for others to understand.

Interestingly this language was introduced to a wider audience in the 1950s by Kenneth Williams, who used Polari in his comedy skits in ‘Round The Horne’, a popular comedy programme on the radio hosted by Kenneth Horne, where he and Hugh Paddick played a pair of Polari speakers called Julian and Sandy. As well as this, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore used Polari in their comedy sketches and books.

These sublanguages weren’t used for fun; they were used for safety. You may have heard bits of Polari and Yiddish here and there, but how much of the origin of the language is known? In environments and times when laws were different to how they are now, the best way to ensure protection was to use coded language.

A Clockwork Orange was not the only time authors have used a different slang language to write in. Although Nadsat was a fictional sublanguage, the author of ‘Man-Eating Typewriter’, Richard Milward, makes sure the coded language of Polari stays important, by including it in his recent book.

Man-Eating Typewriter by Richard Milward

Set in the late 1960s, the story of Raymond Novak and his threatening memoirs is told entirely in Polari. This book within a book full of violence, disturbance, and unapologetic galavanting. Richard Milward never fails to delve deep into a world of pulp fiction, simultaneously allowing us to see into the language of Polari alive and vibrant and used as a gateway to explore the effervescent but mad Raymond Novak.

The protagonist is not gay per se, but he is part of the Navy, where Polari was the general communication tool ‘below decks’. In a time in London that was bleak, dark, and post the 2nd world war the book is written from both a publisher’s perspective and the words directly of Raymond from his book and life story.

He talks of the plan to commit a ‘fantabulosa crime’ in 276 days that will shock the nation. As his memoirs, which we read within the novel, become increasingly more disturbing, the use of Polari shows also the eccentric world he ran in.

Incredibly written in a way that readers can follow what is going on even without much of an understanding of the language of polari, its twisted lines engulf the reader into a world of adorable nonsense, a slightly scary madcap ideal and an underworld that is as grimy as it is funny.

Brilliantly crafted and interwoven with exquisite plays of language; the writer Richard Milward pulls the reader deeper and deeper into the darkening mind of his leading ‘gentleman’ Novak. As absurdist as Dada, and as funny as Round the Horne, but weird and dirty enough to slightly turn the tummy of ‘slight polite company’.

It’s fascinating how language absorbs the community around us; how it’s used in different ways to be secretive and comforting to hear in times when you feel out of place.

Some languages such as the universally introduced Esperanto allowed us to come together with one global language spoken across the world. This global language was supposed to be spoken by many different countries except the concept never really took off.

Whether it’s a native language you know from family, or just text abbreviations you send a friend, a community with its specialist ‘speak’ is very much wrapped in a sense of self. And it’s vitally important to keep identity and community within our world.

Read more about Richard Milward’s book, ‘Man-Eating Typewriter’ and buy it here via White Rabbit.

Read more about Alan Weber’s The Mensch here

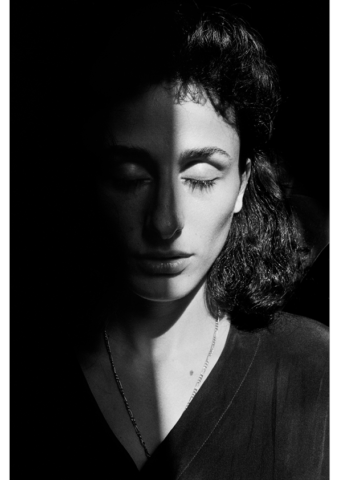

Cover image by Nhung Nguyen for a series of images to come out as a collaboration with Richard Milward and Cent Magazine.

If you liked Speaking In Code, why not try Internationally Indisputable.

.Cent London, Be inspired; Get involved.